I’m deep in the problems and working-out phase of a new novel. I’m plotting and getting words down and deleting them and moving things about. This isn’t a new process for me, but the way I am approaching it is: trying to nut out problems and find solutions earlier than I usually do. In the past, I’ve written my way into the work - more like ‘pantsing’ than ‘plotting’ - which works for me but also takes a lot of time, lots of words and lots of dead ends. I’m trying to be more efficient this time around - in part because I have a shorter deadline, but also because I reckon it’s a good creative experiment.

In his Story Club post this week, writer George Saunders (who I had the great privilege of interviewing for the First Time podcast here) wrote about his approach to solving a ‘potentially book-ruining problem’ as he wrote Lincoln in the Bardo. It’s an excellent post and well worth a read if you’re a paid subscriber (which I highly recommend becoming if you can!).

Why me? Why this? Why now?

As part of my doctoral research on shape and structure and how I put The Hummingbird Effect together, I’ve been writing about the ‘problem’ of realising the novel I wanted to write was something altogether different from the manuscript I had produced and how I was inspired by the work of artist Paul Klee to try a different form.

When I talk about this process at events and with other writers there are always lots of questions and sometimes even aha moments, so I thought I’d share a little of that work here. If you’ve read The Hummingbird Effect and look closely at the images you’ll notice that I made many more changes after this process - to shape and plot, words and characters. For example, there’s no longer a monk’s clock, or Percy’s 1917 story - which I referenced in my last post. But as a ‘slice of the process’ (which we sometimes call it in PhD land) I’m hoping this is helpful to other writers looking at restructuring their work, or creatives looking to other mediums for inspiration for their own art.

Finding Klee

Klee was a new-to-me discovery; I didn’t know his famous painting Angelus Novus, and yet as I read his collected notebooks The Thinking Eye (1961) and The Nature of Nature (1973) and pored over his drawings and paintings online, I felt I could see the kind of shape my novel-in-progress might eventually take. Specifically, the way in which that shape might help create connection between ideas of cause and effect, progress, circular time and inheritance that were key to the novel.

I came to Klee via an Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on progress where I first read the words of Walter Benjamin in his Theses on the Philosophy of History:

A Klee painting named ‘Angelus Novus’ shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing in from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such a violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.

Benjamin, 1941, p. 257–8

Benjamin’s description and the eerie Klee painting both spoke to the ideas I wanted to explore in the novel: how we are shaped by the past, who we are now and who we might become, the idea of the ‘storm of progress’, turning one’s back on the future and being blind to the consequences of the damage we sow today. And kind of magically I thought, the word ‘chain’ appeared, a touchstone of the novel in terms of automated factories, labour and generational inheritance. The words and image had the elements of ‘heat’ I associate with material I need to pay attention to during the creative process. Charlotte Wood describes this ‘heat seeking’ aspect of the creative process as “the way artists separate promising from unpromising material by sensing and following the ‘power’ or ‘energy’ coming from any part of the work” (The Luminous Solution, p 27). Going to the heat is a big part of how I write.

I was immediately drawn to Klee’s deep interest in form and structure and his articulation of the creative process in phrases which I madly copied into my working journal:

Genesis as formal movement is the essence of the work of art. (17)

The truly creative person works with the lapidary quality of language not with its multiplicity. (449)

…do not think of form but of formation. Hold fast to the path, to the unbroken connection with the original ideal. Thence carry the formative will onward with the force of necessity, until it permeates the particles and parts. Step by step, carry it from the smallest to the larger, press forward until you have penetrated the whole; keep the formative line in hand, hold fast to the creative stroke. (454)

This new ‘Klee’ lens of looking at the freshly exploded novel opened up possibilities of forming the material of the novel into a shape that best expressed its internal logic and meaning; questions on the nature of progress (destructive or benevolent), chains of women’s connection through labour over time, machines, entropy and resistance in all its forms.

As I read and worked, I experienced what friend and writer Penni Russon, described as a ‘haunting’ by Klee; references and mentions leapt out of texts I picked up, even those I have read before when I had not recognised Klee’s presence. Writer and blogger Austin Kleon creates images which visually present complex ideas, and his books on the creative process – Steal Like an Artist (2012), Show Your Work (2014) and Keep Going (2019) – are ones I often recommend.

In Kleon’s post, Inscrutable Blueprints, he references Klee’s diagrams and also those of John McPhee, a writer whose work was hugely influential during my research for The Mother Fault – both the geological content of his epic Annals of the Former World and his writing on structure in Draft No.4: On the Writing Process. Seeing these two thinkers together in Kleon’s post validated my feeling of ‘being in the right place.’ Likewise, only when it was pointed out to me, did I realise I had seen a reference to Klee’s Angelus Novus before; it appears in Ruth Ozeki’s The Book of Form and Emptiness, a book I had read and admired, and also a writer I’d been reading specifically for her interest in abattoirs in her novel My Year of Meats. Yet another Klee ‘haunting’ occurred when I went back to reread Annie Dillard’s descriptions of observing the stunt pilot Dave Rahm in the final chapter of The Writing Life, and how the experience shifted her ideas of beauty and human possibility. She describes the pilot and plane as being like “a Klee line, it smattered the sky with landscapes and systems” (95). I’d read this chapter many times and never before had this reference made such perfect sense to me, nor had I fully appreciated the fact that Dillard was conceptualising form and line in a new way after witnessing Rahm’s flights;

he furled line in a thousand new ways, as if he were inventing a script and writing it in one infinitely recurving utterance until I thought the bounds of beauty must break.

Dillard, The Writing Life, 2009. p.109

These different Klee hauntings lead to a feeling of serendipity or ‘rightness’ and suggested that my circling of ideas and images for this novel might serve as some kind of map. The postscript to these Klee hauntings came during my Michael King Writing Residency in October 2022, where I found a first edition of Klee’s notebook in second-hand bookshop Bookmark after much searching. The smile says it all.

The reshaping experiment

Using Klee’s idea of formation over form, I approached this new shaping of the novel as an experiment, with no expectation that the structure I arrived at would be anything other than a part of a longer process. I wanted to begin this restructure with a printed copy of the manuscript laid out on the floor and worried that the only space big enough to do this at home was the hallway, which would artificially force me to think about the layout in a linear or chronological way, so I went to my parents’ house and used a room large enough to allow me to spread the manuscript out in different shapes.

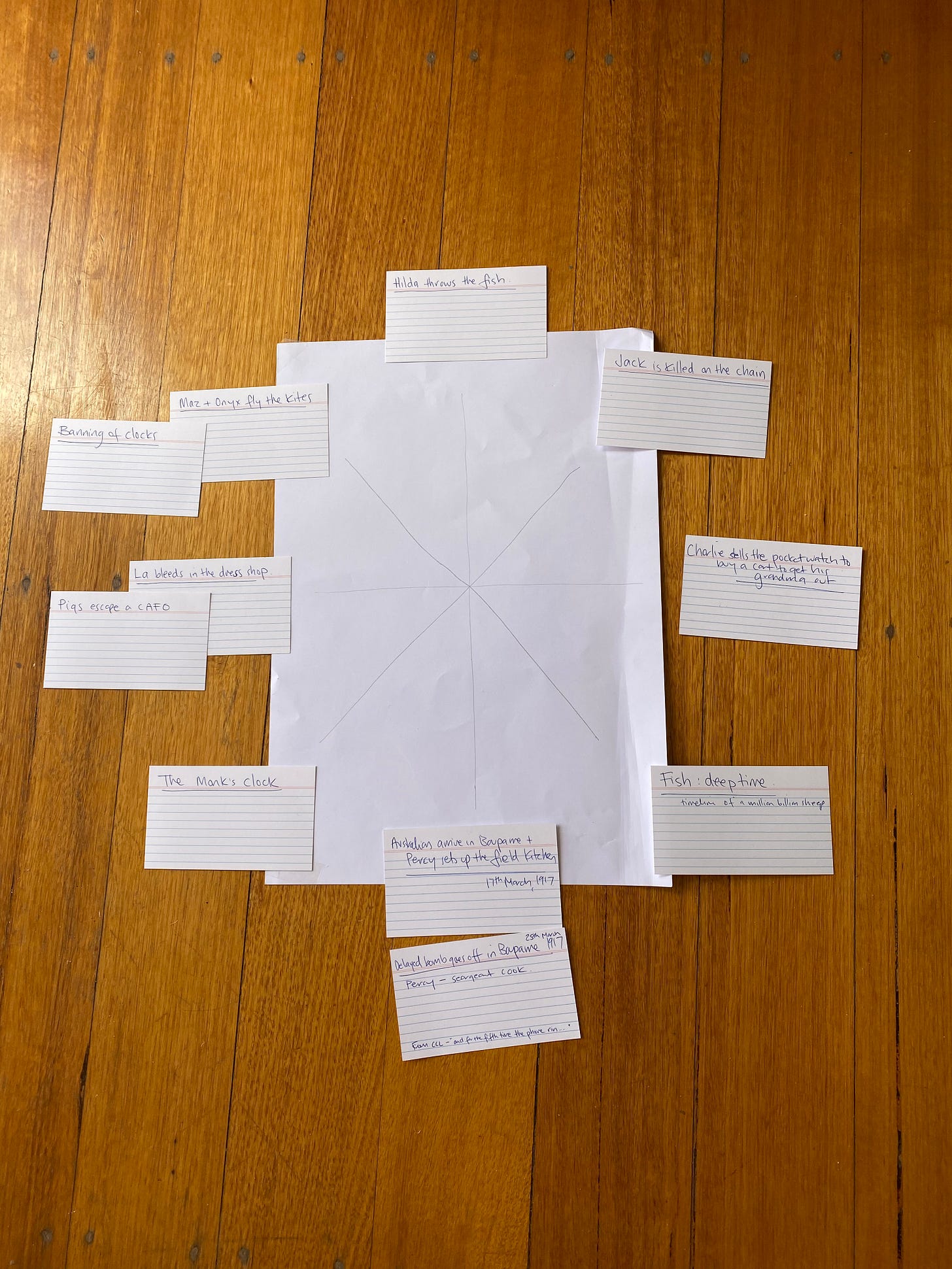

The physical laying out of a manuscript has been part of my creative process since writing The Mother Fault, when I was struggling with managing the size and complexity of the novel within a word document. I’d read and loved Anne Lamott’s chapter ‘Plot Treatment’ in Bird by Bird where she lays out her ‘failed’ manuscript on the floor and moves it around until it makes sense to her. I thought trying this process myself might help. I’ve also participated in a number of workshops with one of my faves, US writer Sarah Sentilles who often talks about her ‘cut and tape’ writing process where she prints out her writing fragments, arranges them by theme and then ‘Frankensteins’ them back together. I’ve always written straight into word documents, and while I’ve tried software such as Scrivener and Trello which give visual organisational structure to work in progress, I find them difficult to work in and ultimately unhelpful for me. Touching the material itself – printed paper, index cards, the pen and highlighter – allows me to see the whole work more clearly.

Circles and stars had been shapes resonating with me during the writing of the novel. The star shape was introduced to me by Brian, who I met on the beach during a writing retreat at RMIT’s McCraith House where I exploded my manuscript and accepted that the novel was the not the straight, chronological historical narrative I had initially intended it. When I described the problem of not knowing how to put my manuscript back together Brian drew me a star shape. ‘It’s simple,’ he said as he drew the first line in the sand, ‘you start here and then follow the line.’

Still sandy and wet from my swim, I went back to my desk and laid out the sketchy index cards of each narrative in this shape. It was the first of many lightbulb moments.

Another image I’d saved was of a wind rose diagram I used as part of my research for the far-future narrative strand which (at that stage) involved wind power.

There was immediate synergy with the visual similarity between the wind rose diagrams and Klee’s colour wheel:

Both shapes show pattern and repetition with a randomness that appealed to me. When I noticed how often circles appeared in various forms in Klee’s notebooks I decided that the circle was the shape which might best ‘hold’ my novel-in-progress. Both of these images were ones I used as part of an Artist Statement created in a Sentilles workshop, and which became a touchstone for the rest of the writing.

On the floor at my parent’s place, I began by splitting each narrative into four sections - a ‘teaser’ plus three act structure. I then laid each out narrative as if the parts were spokes on a wheel, or sections of a clock. I placed the fifth ‘lecture’ narrative between the spokes (the ‘lecture on a cruise ship’ narrative morphed into the AI story later). While the balance in this shape was aesthetically pleasing and made sense for the narrative, I wondered how to translate this into the constraints of the codex - reading from first page to last. Where does a shape like this begin, and end? Does it follow each spoke out and back in? Or circle out from the centre?

As I played with the position of the narrative sections I continued to return to Klee’s notebooks, skimming for ideas relating to movement, chronology or direction. I was looking for possible arrangements and sequencing of the narrative parts that might illuminate new meaning, or help me feel like the puzzle had been put together. I looked for arrows, unbroken lines and the kinds of shapes and connections that had already appeared in the work and process. With new pencils (I don’t know why new pencils are essential but they are!) and paper, I drew the shape I had mapped out on the floor and then tried to connect it with an ‘unbroken line’ as per some of the instructions in Klee’s lectures and notes.

Moths and butterflies are recurring images within the novel, something I had only really recognised during the reading of the full draft. Combined with the imagery of the angel with outstretched wings from Klee’s Angelus Novus, I could see how the messy line I had followed was reminiscent of wings. I tried the drawing again and was exhilarated by the clear wing shape the arrangement formed.

While the wing shape was satisfying and introduced the idea of the novel being separated in two mirror halves, it did not solve the direction or sequencing of each of the narrative threads. My original arrangement had each ‘spoke’ beginning with the 1933 story closest to the centre then moving outward through near future (2031) back to 2020 and finally to 2300, with the lectures interspersed between each spoke. I wondered if the mirror image might offer some clue as to how I might arrange these narratives in a way that added more meaning to the story, both in the sequence, the places the stories ‘touched’ and in the gaps between. Further skimming of Klee’s notebooks led me to this lemniscate figure:

Particular words and phrases in Klee’s accompanying description - ‘balance’, ‘interlocking’ and ‘polyphonic overlap’ - resonated with the connection I wanted to make between the separate narratives. Creative writing scholar, Kate Cantrell, describes the lemniscate figure as a

horizontal figure eight… a curve that moves continuously forward as it moves continuously backward. This movement elicits a non-linear narrative that is characterised by a forward progression through space and a backward passage through time. (2014 2)

I attempted my own version of the figure, and then blocked in how the narratives might fit in this sequence.

I rearranged the floor map to reflect this drawing; now the first ‘wing’ started in 1933 (Peggy & Lil), moved to 2031 (La & Cat), back to 2020 (Hilda) and then to 2300 (Maz & Onyx), before coming to the central point (the lecture) then moving back through 2300, 2020, near future and 1933 and returning to a lecture at the centre or midpoint of the novel. The opposite wing began in 2300, moved to near future, then to 2020 and 1933, the lecture point, and returned for the final part of the novel via 1933, 2020, near future and finally 2300. Immediately there were new and satisfying juxtapositions and connections between the narrative parts.

The speed and playfulness with which I did this entire restructuring activity over one day allowed me to hold the novel’s shape and content in mind and I finished satisfied that I could begin the new redraft of the novel in its entirety with this shape as a guide. The final act of this restructuring experiment was to create a contents print out of the manuscript reflecting the new structure.

During the various phases of writing the novel, I printed out these chapter outlines at points where I have made significant changes, additions or deletions to the manuscript, so that I had physical documentation of key points in the process, and to be able to mark up during the next phase of writing and editing. This post-restructure print out was the thirteenth in the documentation of the novel (there were many more to come!).

As noted, there was lots more movement and change in the draft after this process, but it remains a transformative point in the writing process of The Hummingbird Effect - where I finally understood how the seemingly unconnected narratives could become a whole.

Creative experiment

What experiments and strategies do you use when shaping your work?

Do you draw from other artistic mediums for inspiration at this phase?

How has playing with shape helped you find meaning in your work?

Try sketching out the shape of your work in progress. Or, the shape of a book you love (Michael Christie’s Greenwood was another touchstone for me - helpfully his contents page shows the shape as a cross section of a tree trunk, something we talk about in this interview).

Write the sections of your work in progress on index cards or post it notes and shuffle them around in different shapes. Experiment with unlikely or ‘impossible’ shapes. Jane Allison’s Meander, Spiral, Explode: Design and Pattern in Narrative is an excellent read if you want inspo.

Take a narrative - your own or someone else’s - you know well and play with new shapes you might use to tell it. What meaning do the new gaps or meeting places between sections reveal? How does the new shape change the pacing, the reading experience, the character arcs?

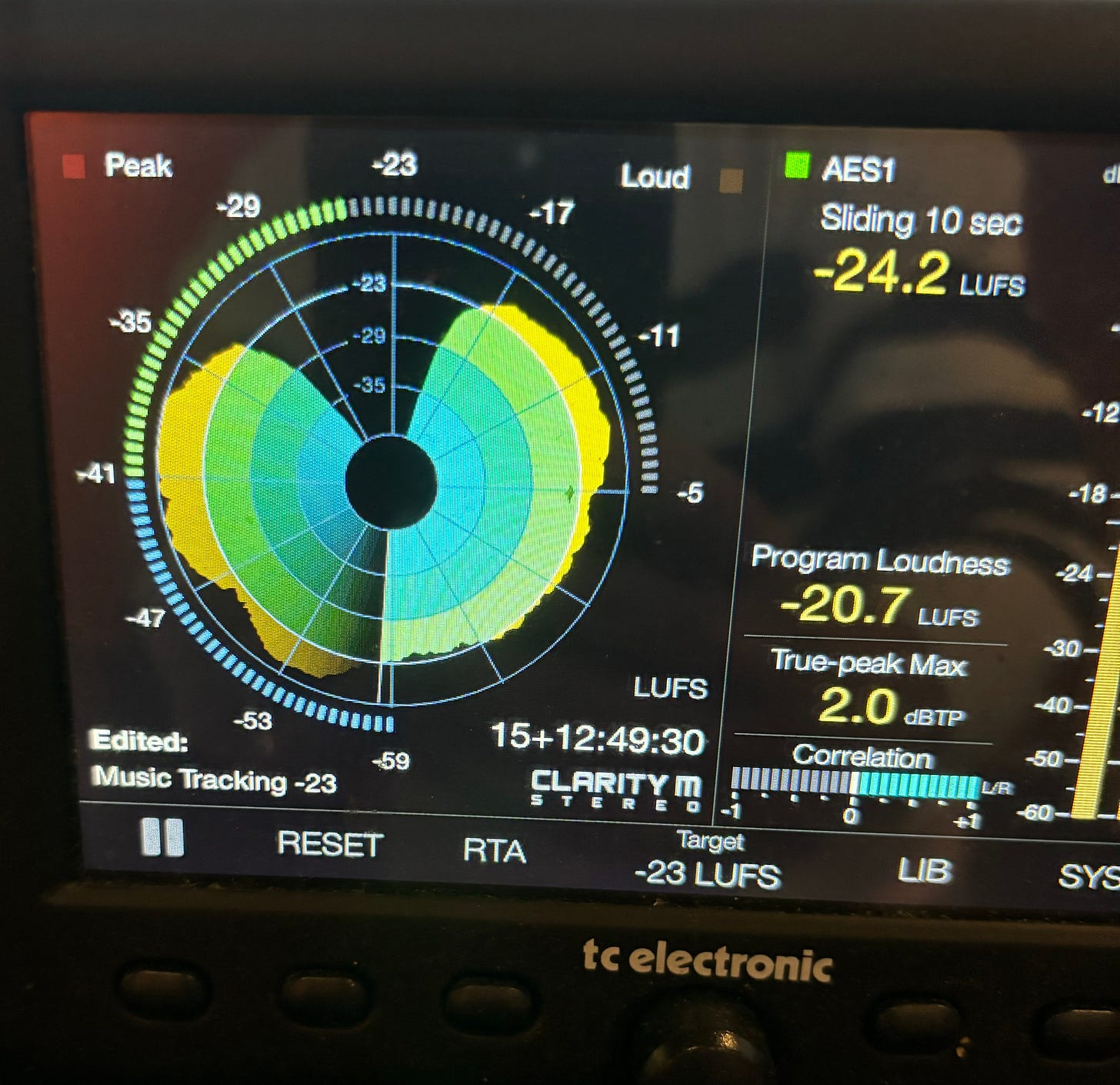

Pay attention to shapes you encounter in your day: in the natural world (I took much inspo from leaves and flowers at one point!), from science or other fields outside your own (as a final moment of serendipity, last night in an ABC radio studio I noticed this image - wings, wind roses, colour wheels!):

Would love to hear from you if any of this resonates or if you’d like to share your own experiments in the comments!

Until next time and with love, K xx

Thanks Kate! I was about to reply w/ a note about Kate Cantrell's work on the lemniscate! She's brilliant. And totally different but I think you'd like this book by Anthony Mullins: https://www.avidreader.com.au/p/beyond-the-hero-s-journey-a-screenwriting-guide-for-when-you-ve-got-a-different-story-to-tell?barcode=9781742236995&search_key=beyond+the+her

Yet another great read and lots of tips to consider and try - it’s a bit overwhelming and I’ve never worked like this before but maybe something like this is just what I need to try! Thanks for sharing and being so generous 💕